Snip!

Coach Mike Korbach closed the scissors on the last loop connecting the net to the basketball hoop, then he held the net high overhead. College basketball champions at last! Pandemonium reigned as the crowd surged and celebrated beneath his stepladder perch. He pumped both arms in the air and added his voice to the uproar—which was abruptly silenced by a tentative knock at the door.

Coach mentally climbed down from the ladder in the photograph he held in his hands. He was sitting at his desk in a small room with olive-green concrete block walls. He set the photograph down and said, “Come.”

The door opened, letting in the sound of fiddle music and stomping feet from the junior high school gym. Dale Martin stood in the doorway. Debate team kid. Tall, fairly athletic, smart, but he wouldn’t come out for basketball. Wasted potential. Right now, his posture was oddly formal, like that of the new ambassador from a tiny island nation.

Coach said, “Martin. What’s wrong? You got stomach trouble?”

Dale said, “Miss Cheever says to tell you we need an extra boy.”

“An extra boy? For what?”

“Square dance lesson. There’s twenty girls and nineteen boys. Missy Evans has no partner.”

“Are you telling me not one girl wants to sit out gym class? Not Missy or any other girl? Alert the newspaper.”

Dale shrugged and said, “I’m just supposed to tell you we need an extra boy.”

Coach said, “There’s not a group dance where everybody can just jump in, maybe run in circles like in Oklahoma? Break a sweat, run out the clock and call it a day.” He pantomimed running with a gleeful expression.

Dale laughed and said, “All we have are the old square dance records with the diagrams. And it’s Miss Cheever, you know. She probably doesn’t know any other dances.”

Coach said, “It’s not like I have a spare boy in the equipment locker. Tell Miss Cheever the girls can take turns sitting out.”

Dale said, “Sir,” and backed out of the office.

Coach picked up the photograph and settled in for more meditation. His idol atop the ladder had also put in time teaching junior high gym. It was in his autobiography. No mention of being required to teach dance movement.

Less than a minute into his reverie, another knock at the door.

Coach yelled, “What?”

The door swung open. Dale Martin regarded Coach warily.

Coach waved him in. He said, “Fear not. What is it now?”

Dale emerged from his defensive crouch and said, “Did I mention that she’s crying, Coach?”

“Miss Cheever? You weren’t gone long enough to tell her what I told you to tell her.”

“No, sorry, sir. I remembered I was also supposed to tell you before that Missy Evans is crying. Remember her? She’s the twentieth girl. The one with no partner?”

“I remember that, Martin, thank you. But why would that make her cry? I would be begging to sit out that crap. I mean that learning unit. I do sit it out.”

Dale said, “It’s embarrassing. Like not being picked for a softball team or something.”

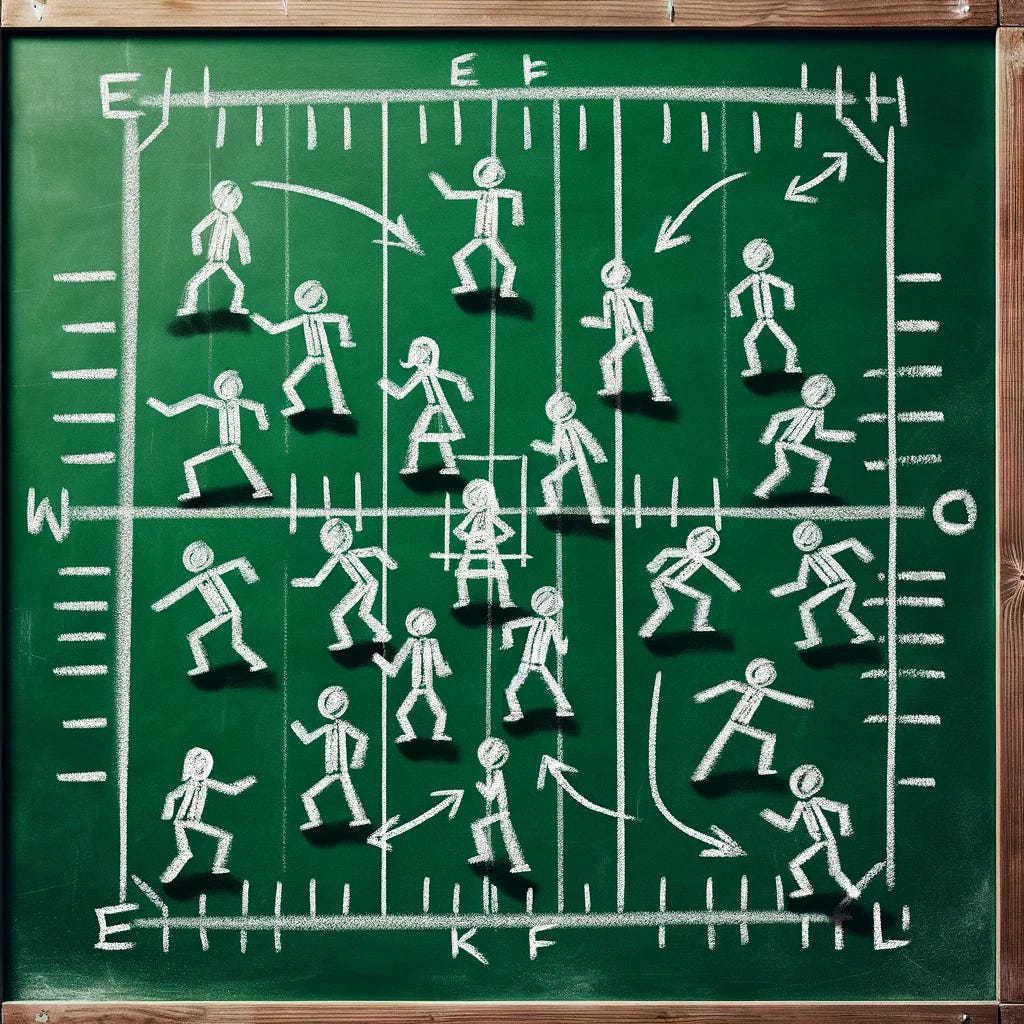

Coach stood with a weary sigh. Did the man on the ladder have to deal with crying girls in square dance class? Heck no. He probably just coached from dawn to dusk. Inspiration! That’s what he would do, too. Coach went to the chalkboard. “New play, Martin. Pay attention.” He rapidly sketched out nineteen Xs and twenty Os representing unbalanced boys and girls. A short line connected each X with an O, except for the twentieth O, which he labeled “M. E.” for Missy Evans.

Coach pointed with his chalk and said, “See, one boy rides the bench. He’s happy because…well, he’s a guy, he won’t mind.”

He erased the line between one paired X and O, then drew a curved dotted line with an arrow on the end, indicating motion, to show that one X had left the field of play. Now there were eighteen boys. He drew a line between the newly-single O, and the O that represented Missy Evans, and explained, “Then, you see, the two extra girls partner up with each other. No more tears.”

He drew two eye dots and a smiling mouth inside the Missy Evans letter O. He smacked the chalk into the wooden shelf across the bottom of the chalkboard, briskly brushed the white dust from his hands, and regarded Dale with arms akimbo, waiting for that magic moment when a good chalk talk flips the “on” switch in a kid’s brain.

The magic moment did not arrive. Instead, Dale approached the board and picked up the chalk. Coach’s face flushed bright red. In the history of organized athletics as he knew it, no player had ever presumed to take up his coach’s chalk. There existed a hierarchy, with clearly-defined roles. Yet here this…this debater…was blithely wielding not only his chalk but he held an eraser in his other hand, and he clearly intended to use both. Coach froze in place, unable to comprehend, and thus also unable to move to prevent, this blasphemy.

Oblivious to his peril, Martin said, “If you pair up two girls, I think both would be crying.” He sketched arcs of tears emerging from the two paired Os. “And what if no guy volunteers to sit out in the first place? You’re always yelling at us about participation grades.” He erased the dotted line, restoring the nineteenth X to the dance floor, then reconnected that X with Missy’s erstwhile female partner. The Missy Evans letter O was alone with her tears once more.

Recovering from his paralysis, Coach vigorously erased the chalkboard as he said, “Oh, for Christ’s sake. Just tell Miss Cheever to buck up and carry on. If pairing up two girls doesn’t work, tell Missy Evans it’s only for one dance.” He added, at the lowest volume he had yet employed that day, “And I don’t yell. I speak with emphasis because half the time you knuckleheads are goofing off and not listening to me.”

Dale bowed out. The next knock came just five seconds later.

Coach said, “Martin?”

Through the closed door: “Yes, Coach.”

“Enter.”

Dale said, “I had an idea. Maybe you could do it, Coach.”

Coach said, “You want me to tell Miss Cheever?”

“No, Coach. I mean maybe you could be the boy we need. I mean, the guy. The man. You know.”

Coach was aghast. “Was this Cheever’s plan all along?”

“No! Well, yeah. I mean yes, sir. She told me to fetch you but I knew you wouldn’t like being fetched. I hoped you would just get the idea.”

Coach looked wistfully at the photograph of his triumphant hero. Even that guy had probably endured a long history of small, cruddy offices with beat up furniture and ancient light fixtures before becoming a college legend. The stepping stones on the path to glory were not themselves necessarily glorious; but some days, like today, the stepping stones could be downright depressing.

Coach refused to give in to the mundane. His own legend had to start somewhere, sometime. He would be a legendary hard-ass, starting now. He gritted his teeth and said, “Hustle back out there, Martin. I have work to do.”

Dale just stood there, smiling that damned ambassador smile.

Coach said, “Did you hear me, Martin? Get out of here. Let me work.” He plucked a pencil from the cup on his desk to symbolize imminent adult work of an unspecified nature, there being no papers visible on his desk.

“No, sir.” Dale boldly sat in the wooden guest chair.

In motivational halftime tones, Coach said, “Now, Martin, you do what your elders tell you to do, you hear? Get gone, or you’re going to be in a world of trouble. Starting with demerits.”

Dale said, “Miss Cheever is my elder too, and she’s in charge of the class today. Meaning no disrespect, but I feel like somebody’s going to give me demerits either way. It’s a matrix. Your way, I get demerits and Missy Evans is still crying. If you join us, maybe I get demerits for disobeying you or maybe I don’t, but Missy’s not crying. On the other hand, if you do nothing and I just sit here, the class evens out by default and you don’t get any work done and maybe I get demerits…”

As the boy’s amazing litany of mutually reinforcing arguments unfolded, Coach tipped a mental cap to Cheever: Touché, madame; you chose your messenger well. Coach finally held up his hands to stop the rising tide of rationalization before it drowned them both. He and Dale stood and regarded each other like a groom and his best man in the final private moments before a shotgun wedding. It was unclear who initiated the formal handshake they exchanged. Perhaps the moment simply demanded it.

Then, together, they marched toward the sound of fiddles.

—30—